I was recently exposed to the idea of Non-Fungible Tokens (NFTs) through Twitter. I’ve struggled to wrap my head around them ever since. What does it mean that people are willing to pay millions to own a Tweet or JPEG? How does that sentence make any sense? And why do the concept of NFTs reliably evoke such polarised emotional reactions?

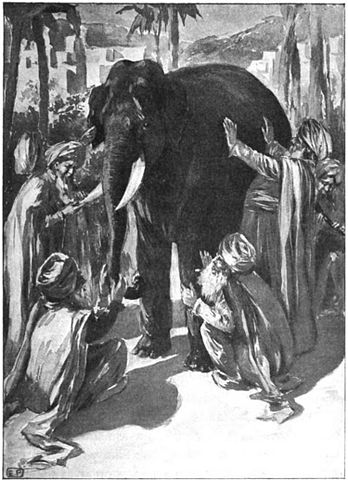

There was a recent article featured on Hacker News titled NFTs Are a Dangerous Trap. This was useful, but perhaps more for the comments it generated than for the article itself. The comments represented a wide range of perspectives, often passionately and intelligently argued for. Like the parable of the Blind men and the Elephant, it’s useful to listen to a number of voices when something new and mysterious is encountered. Each one might have a grasp of part of the truth. It’s also possible the new thing is in fact many things all at once.

The Blind men and the Elephant

After some reading and thinking, the conclusion I started to come to was that NFTs aren’t hard to grasp for technical reasons – at least not primarily.

Rather, NFTs are hard to grasp mostly because of the strangeness of the more fundamental ideas they rest upon – ideas like ownership and value. These are ideas that have, until recently, been easy not think too much about. NFTs have changed this by being so difficult to ignore.

Is Ownership Real?

To test this theory, let’s forget about NFTs for a second.

What does it mean to “own something”, really? How does the concept of ownership map onto the objective, material world, if at all? When you get down to it, does owning something just mean the ability to defend access to it through the threat of physical force? It could be you, your family, friends, hired guards or the state that wields this force. In any case, it’s hard to imagine ownership would count for much if it couldn’t ultimately be enforced physically.

It could be argued that direct, physical force isn’t needed to enforce ownership. Imagine children playing the board game Monopoly. If one child openly steals the other’s Monopoly money, the other children will soon refuse to play with him. Social exclusion is really painful; it appears to activate the same areas of the brain as physical pain [1]. This makes a lot of sense from an evolutionary perspective. Exclusion from the social group means a lower chance of survival and of finding a mate. Direct physical force might be more obvious and easier to observe, but the effect is the same in both cases – pain, potential harm and death.

So on one hand ownership is “merely” an abstract concept, a social contract that we act out. It’s not something concrete you could point to in the external world. On the other hand, violating it leads to undeniably real and painful consequences. Given this, is it so unreasonable to act as if it were just as real as something you could feel, smell, taste or see (to quote Morpheus)?

Is Value Purely Subjective?

Another, equally mysterious topic rudely forced onto us by the arrival of NFTs is that of value. What makes something valuable? Is this value “real” or something purely subjective, reliant on collective whim, at risk of evaporating at any moment? If so, is this true of everything valued? Or are some things really, intrinsically valuable, independent of anyone’s opinion?

I suspect these questions are difficult because they can’t be easily reconciled with a scientific, materialist view of reality – the dominant view of our culture. They would sound absurd to someone from a pre-scientific time. “Of course those shining gold bars are really valuable. Just look at them.”

To borrow an example, imagine Elvis Presley’s guitar. It is functionally identical to thousands of other guitars like it, yet it is far more valuable. Is this value “real”? If it is, it can’t be due to the physical properties of the object itself. Its value isn’t intrinsic to the object, much like how paper money isn’t intrinsically valuable. You can’t do anything with it that you couldn’t do just as well with any other guitar (from a narrow, utilitarian perspective at least).

Is it valuable then merely because enough other people agree that it is? Then how does this agreement come about?

There seems to be some relationship between an item’s uniqueness or rarity and its value. Could this be the reliable, objective foundation on which broad agreement on value rests? There was only one Elvis Presley and that was the one (generic, mass-produced) guitar he played.

However, on further inspection this uniqueness/rarity theory doesn’t hold up. Why? Because the same could be said about any second-hand guitar – that it was once owned by a unique person. Only, say, John Doe from down the street instead of Elvis.

So being associated with a unique individual isn’t enough, there’s more going on here. An obvious omission is that Elvis is widely recognised as an important figure in popular culture, unlike John Doe (in Western culture at least – more on this soon). Why does this matter though? Why does this mean that more people would be willing to expend more hours of their labour to own his guitar? Perhaps because there are many more people with a positive emotional connection to Elvis and his music – his guitar has sentimental value for them. Seeing Elvis’ guitar hanging up in their house would make them smile and feel a sense of pride. It would also reliably communicate something to others and themselves about their identity.

You could go further still and make the case that the new guitar owner’s positive emotions are due to their increased social status. This increase in status translates to increased survival and reproductive opportunities, etc. Though perhaps this isn’t necessary; it’s enough to simply recognise that the expectation of positive emotions and a buffering of one’s sense of identity are part of what makes something valuable.

Are iPhones Intrinsically Valuable?

Earlier I said that Elvis is widely recognised as a important figure in Western culture at least. Conversely, it’s not hard to imagine a remote, isolated culture where Elvis is unknown and his guitar has no use other than as firewood. The same is true of objects we might think of as having “intrinsic” value – a BMW or an iPhone let’s say. Move these objects to somewhere without electricity, gas and internet access and they become basically worthless. So their “intrinsic value” is revealed to be nothing of the sort. The value of an iPhone is just as contingent and dependent on a particular context as Elvis’ guitar.

So is there anything with intrinsic and objective value, that is valuable for all people at all times – past, present and future? What about food? This is more of a stretch, but it’s not impossible to imagine a future where Elon Musk’s Neuralink reaches the point where it’s possible for us to transplant our consciousness into a machine. Food as we know it today would then be worthless.

Where Two Worlds Meet

It’s as if the question of value has no bottom. The more you think about it, the more questions are raised and the more mysterious it becomes. It’s indefinitely deep. NFTs have opened Pandora’s Box, and the mysterious nature of value is one of its contents.

To repeat, I suspect such questions are difficult to us because they can’t be easily reconciled with a purely scientific, materialist worldview. In order to objectively explain events in an independently-reproducible way, it’s necessary to eliminate the subjective human experience from consideration as much as possible. This is by design, and is necessary for science to function.

But try to measure the value of a guitar from an objective standpoint – it’s not possible. Any question of value must involve a subject. And while an item’s value isn’t objective, it cannot be easily dismissed as “merely subjective” and therefore irrelevant. The value of a stack of papers with pictures of the Queen might not be observable or measurable in a lab, but try throwing it into a crowd. Their resulting behaviour will most definitely be independently observable, measurable – and relevant to a living person.

A final leap of wild speculation. Could it be that NFTs have done nothing less than expose a place where the objective and subjective (or concrete and abstract) worlds meet, showing them to be part of the same world, not quite so distinct and irreconcilable after all? And all in a way that’s difficult to ignore.

References

[1] Feeling the Pain of Social Loss – Jaak Panksepp et al.